The Justice Department is demanding states surrender their private voter data in the name of election integrity. But its rapidly expanding crusade to seize that data has been riddled with sloppy filings and a growing list of self-inflicted embarrassments that undercut the department’s claim to competence.

Over the past months, the DOJ has launched an unprecedented national campaign seeking unfettered access to voter records, suing election officials in 21 states plus Washington, D.C. Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Harmeet Dhillon has framed the effort as necessary to enforce federal law and warned that every noncompliant state will be sued.

But as the lawsuits have multiplied, so have questions about the Justice Department’s execution of the campaign. Across correspondence, court filings and public statements, the DOJ has stumbled repeatedly — sending requests to the wrong offices, misidentifying officials, citing fake federal statutes and leaving behind a trail of clerical and legal errors that have increasingly undercut the department’s claim to be safeguarding elections.

“Courts expect Justice Department lawyers to act honestly, in good faith, and to follow proper procedures,” Stacey Young, executive director and founder of Justice Connection, a network of Justice Department alumni, told Democracy Docket. “Mistakes in court filings – from small to large – can result in courts losing that implicit trust. If a lawyer is not careful enough to catch these mistakes, it makes the court question the validity of the facts and legal arguments in the filing as well.”

The Trump DOJ’s pattern of incompetence extends beyond voter rolls. Earlier this year, a federal court eviscerated the department’s intervention in Texas’ mid-decade gerrymander, finding that a letter signed by Dhillon was “challenging to unpack because it contain[ed] so many factual, legal, and typographical errors,” and effectively handed voting rights groups the evidence they needed to block the GOP’s gerrymander.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court later set aside the ruling that blocked the gerrymander for the 2026 midterms, it never endorsed the DOJ’s reasoning or defended the letter itself — leaving intact a scathing judicial record of carelessness at the top of the Civil Rights Division.

Against that backdrop, the DOJ’s voter roll crusade reads less like a carefully executed enforcement effort and more like a cautionary tale in institutional sloppiness. From misdirected demand letters to unexplained personnel confusion to filings that appear to have skipped basic proofreading, the department’s mistakes are piling up — even as it insists states must meet its exceeding authority or face federal suit.

Asking the wrong people for the wrong records

If the Justice Department wants states to trust it with their most sensitive voter data, it has repeatedly struggled with a basic prerequisite: knowing who actually runs elections.

In July, the DOJ sent a demand for election data to Wisconsin Secretary of State Sarah Godlewski. There was just one problem — Godlewski does not oversee elections in Wisconsin. That responsibility belongs to the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission, a structure that has been in place for years and is well known to anyone familiar with the state’s election system.

Godlewski’s office blasted the outreach, calling it part of “a coordinated and cynical witch hunt about the 2020 election.” The email sought information on allegedly ineligible voters and potential election fraud — despite being addressed to an official with no authority over the records requested.

The Wisconsin misfire was not an isolated incident. On the same day, the DOJ sent an identical email to Rhode Island Secretary of State Gregg Amore, and similar messages reportedly went out to multiple Democratic secretaries of state nationwide — a mass mailing that appeared to assume, incorrectly, that all states organize elections the same way.

The sloppiness carried over into formal letters demanding voter registration lists.

In August, the DOJ sent Minnesota a letter threatening legal action if the state did not turn over its voter registration list. In a footnote meant to reference a prior DOJ communication with Minnesota, the department cited a letter sent to “Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk Dean C. Logan” — an election official in Los Angeles County, California, who has no connection whatsoever to Minnesota. The reference appears to be a copy-and-paste error lifted from an unrelated California letter.

Then there is the DOJ’s recent effort to seize 2020 election records from Fulton County, Georgia.

In court filings, the DOJ quietly acknowledged that its initial voter records demand had been sent to the wrong entity altogether. The department first directed its request to the Fulton County Election Board — only to later realize that the physical ballots and envelopes it sought were actually controlled by the Fulton County Clerk. After being redirected, the DOJ resent the same demand to the correct office and, when it did not receive a response, filed suit anyway.

Figuring out who’s in charge

Across the DOJ’s sprawling voter roll lawsuits, the department has repeatedly contradicted itself about the titles and roles of officials leading the effort — sometimes within days of one another, and sometimes in filings submitted to different federal courts on the same day.

Take Maureen Riordan, the former Acting Chief of the Voting Section. In several complaints, including the one against Vermont, Riordan is listed as “Acting Chief.” But in other cases, the DOJ quietly downgrades her title. In the Maryland complaint filed the same day, Riordan is identified as “Senior Counsel.” In Pennsylvania, an earlier case, she is listed simply as “Counsel.”

Meanwhile, Eric Neff, the new Acting Chief of the Voting Section according to the DOJ’s website, is identified as a “Trial Attorney” in some filings, “Acting Chief” in others or simply missing altogether with no explanation.

The confusion is not merely historical. Even as the DOJ’s own website now lists Neff as acting chief — ostensibly replacing Riordan — a filing submitted just this week in California’s redistricting case still identifies Riordan as the Acting Chief of the Voting Section.

Leaving draft comments in official court filings

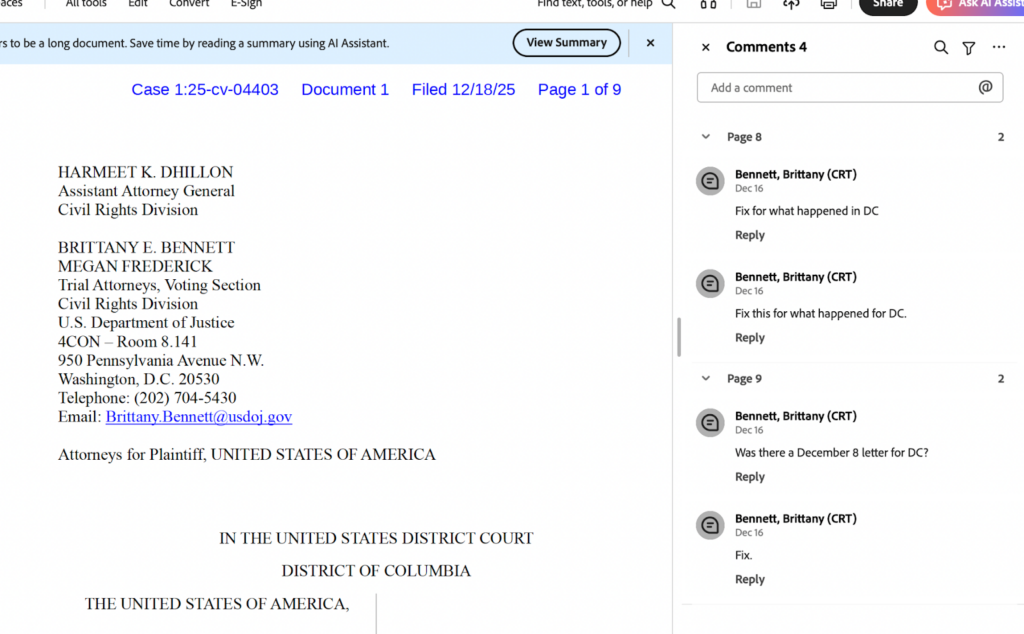

Even by the DOJ’s own low bar in this campaign, what happened in the Washington, D.C., voter roll case stands out.

In filings submitted to federal court this week, DOJ attorneys left internal drafting comments visible in the final documents — revealing last-minute confusion, uncertainty about basic facts and reminders to themselves to “fix” unresolved issues before filing.

The comments appear throughout the documents, including notes questioning whether a key letter even existed, reminders to clean up errors and directives to “fix for what happened in DC.” One comment asks plainly: “Was there a December 8 letter for DC?”

Another addresses a legal citation problem, noting that the DOJ had relied on the wrong appellate court entirely: “Removed 11th circuit case and used quote from SC case. No circuit case in DC circuit.”

In yet another comment, a DOJ attorney flags a procedural issue with the filing itself, questioning whether the signature block complies with local rules: “I think just one signature is needed and certainly one signature per line would be preferable unless there is a weird local rule I am missing.”

Only after the mistakes were spotted did the DOJ submit corrected versions — quietly attempting to clean up the record after the fact. But the damage was already done. The filings offered a rare, unfiltered look at a department rushing complex litigation into court without resolving basic questions about its own evidence, legal authorities or compliance with local rules.

Citing laws that don’t exist and renaming the ones that do

Even when the Justice Department manages to send its demands to the right place and identify the right officials, it often stumbles over a more basic task: citing the correct laws.

Across nearly all of the DOJ’s voter roll demand letters, complaints and proposed memoranda of understanding (MOU), the department repeatedly refers to a statute it calls the “Driver’s License Protection Act.”

There is no such law.

The statute the DOJ is perhaps trying to invoke is the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act, or DPPA — a federal law governing the disclosure of personal information in motor vehicle records. Outside of the DOJ’s own filings in this campaign, the statute is universally known by its correct name. The department’s use of “License” instead of “Privacy” appears to be a systemic error embedded in its standard template language, reproduced verbatim across states and cases.

The DOJ relies on the statute to argue that federal law overrides state privacy protections for driver’s license information — even as it misidentifies the very law it claims authorizes that override.

And the recklessness goes further. In proposed MOUs sent to Colorado, Utah and Wisconsin, presumably to gain trust with their voter data, the DOJ cites an enforcement provision that simply does not exist. The documents claim that the attorney general has authority to enforce the Help America Vote Act under “53 U.S.C. § 21111” — a section of the U.S. Code that does not exist anywhere in federal law.

The error appears in the same section of the MOU that purports to list the DOJ’s legal authority for demanding full, unredacted statewide voter registration lists.

Misaddressing its demand letters

Before the DOJ’s voter roll campaign reached the courtroom, the department was already tripping over its own paperwork.

In multiple states, the department’s formal demand letters — the documents threatening litigation — contained consistent factual and typographical errors.

In Colorado, for example, the DOJ’s letter was addressed to the “Chief Election Official for the Commonwealth of Colorado,” despite Colorado being a state, not a commonwealth. The error might seem cosmetic, but it underscored a broader concern that the department was relying on boilerplate templates rather than tailoring its demands to the legal realities of each jurisdiction.

Arizona received a similar treatment. In a follow-up letter, the DOJ said it was prepared to grant the “Secretary of the Commonwealth” a deadline extension to hand over their voter rolls, even though the letter was addressed to Arizona’s secretary of state — an office that does not carry that title.

Other mistakes were harder to dismiss as mere typos. In its September letter to Louisiana — one of the states that has already given its voter rolls to the federal government — the DOJ repeatedly misspelled the state’s name as “Louisianna,” a misspelling that appeared throughout the document.

Colorado’s letter also stood out for another reason. While nearly every other state was asked to preserve records dating back to the 2022 or 2024 federal elections, Colorado was uniquely instructed to preserve records related to the November 2000 election — a request that, if taken literally, would require the state to locate and maintain 25-year-old election materials.

The confusion extended to Washington, D.C., where the DOJ’s letters and accompanying press release following their lawsuit repeatedly referred to the District as a “state” and demanded its “statewide” voter rolls. The irony is not lost, particularly given the right’s long-standing opposition to D.C. statehood.

Death by a thousand typos and clerical errors

If the DOJ’s voter roll crusade has been defined by anything, it may be its inability to clear even the lowest procedural bars of federal litigation.

In the Georgia case alone, the department managed to misspell the name of one of its own trial attorneys twice — and in two different ways. Christopher J. Gardner’s name appears in the complaint header as “CHRISTPOHER J. GARDNER,” while the signature line at the end identifies him as “CHRISTOPHER J. GARNDER.” It was a small error, but emblematic of a campaign increasingly marked by careless drafting.

But the mistakes did not stop at typos. Across the country, courts have repeatedly had to step in to flag basic clerical and procedural failures by the DOJ — sometimes before cases could even begin.

In Nevada, the department filed a complaint that failed to include Sigal Chattah, the First Assistant U.S. attorney for the district, among counsel of record, requiring a formal correction. In Illinois, a federal judge immediately struck the DOJ’s case-initiating documents after determining that the complaint and motion to compel were signed by one attorney but filed using another attorney’s PACER credentials — a violation of basic electronic filing rules.

The court ordered the documents removed from the docket and forced the DOJ to refile them correctly.

Similar problems cropped up elsewhere. Courts in Colorado, Hawaii and Washington issued notices of deficiency or advisory warnings after discovering signature mismatches, improperly filed pleadings or attorneys attempting to appear without being admitted to the local bar. In Minnesota and New York, judges flagged that multiple DOJ lawyers were not authorized to practice in the district. In Vermont and Pennsylvania, the department failed to include required summonses, civil cover sheets or proposed orders — the paperwork necessary to formally launch a lawsuit.

In several cases, courts explicitly warned that proceedings would not move forward until the DOJ corrected the errors.

Even when filings made it onto the docket, they often required cleanup. The department has filed errata across multiple cases to fix date errors, correct factual mistakes or supply missing documents.

The cumulative effect has been striking. While the DOJ insists states must meet exacting legal standards and hand over their voter data, it has repeatedly struggled to meet the basic procedural requirements for filing its own cases.

Within and beyond its voting cases, the accumulation of errors has eroded the DOJ’s presumption of regularity, which normally prevents defendants from questioning the government’s motivations for bringing an action.

These are hardly the only missteps by the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division since President Donald Trump returned to power. Dhillon oversaw an exodus of experienced lawyers at the Civil Rights Division — 75% of the attorneys left, leaving the administration to now beg for applicants to an office that was once considered the “crown jewel” of the DOJ.